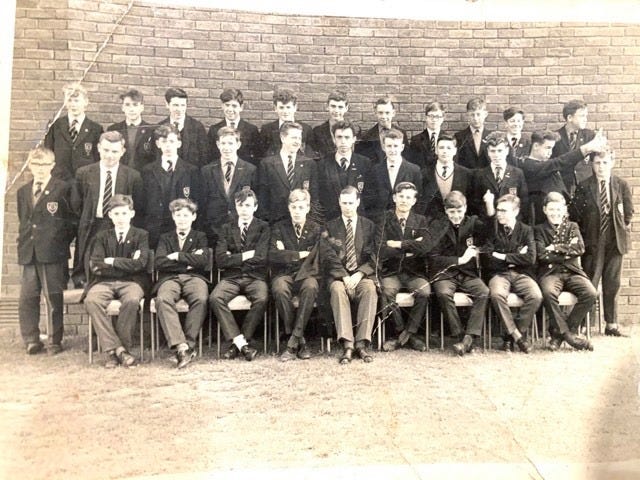

Bliss it was to be alive. Me and the boys in 1966.

WHAT WAS IT about Orangefield school in East Belfast in the 1960s? According to Wikipedia, “notable alumni” of the school include Van Morrison, Brian Keenan, David Ervine, Gerald Dawe, Eric Bell, Ronnie Bunting and even – ahem! – yours truly, Walter Ellis.

I don’t need to tell you who Van Morrison is. He may be grumpy but he is widely acknowledged to be one of the foremost musicians and songwriters of the last 50 years.

Brian Keenan was famously held as a hostage in Beirut for four-and-a-half years, emerging from his ordeal to be a leading Dublin-based academic and bestselling author.

David Ervine, who died much too young in 2007, began his adult life as a UVF bomb-maker, but after a jail-based damascene conversion led an influential peace movement in Northern Ireland.

The acclaimed poet Gerry Dawe, who died earlier this year, spent 40 years teaching Irish literature, most notably at Trinity College, Dublin. His poetry is regarded by many as up there with Seamus Heaney and Michael Longley.

Ronnie Bunting, my one-time pal, whose life and death I chronicled in The Beginning of the End, my memoir of growing up in Belfast, led the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) in Belfast until his murder by Loyalists in 1980.

As for me, I am a retired journalist and sometime author, employed down the years by a number of newssheets, from the Irish Times to the FT.

What unites us? We weren’t any sort of group. We were individuals, from working-class or lower middle-class Protestant backgrounds, who had failed the 11+ and just happened to end up at the same school. Our prospects, back in the day, were not bright.

Morrison was the oldest. I never met him, though I did, some years later, briefly date the girl, living in “that mansion on the hill,” about whom he wrote the extraordinary ballad Cyprus Avenue.

I never knew Keenan either. He was in the “T” (technical) stream while I was sequestered in the “G” (for grammar) stream. But a year or so after Islamic Jihad released him from his subterranean confinement, shared with the journalist John McCarthy and the hapless peace envoy Terry Waite, I interviewed him for The Scotsman. He didn’t remember me at all. An Evil Cradling, his celebrated account of an ordeal spent blindfolded and chained to a radiator, had recently been published and he was already embarked on a successful career in Dublin as a teacher and writer-in-residence at Trinity.

Brian Keenan looks forward

Not only did David Ervine renounce murder and mayhem following his conviction on explosives charges, he went on to enter the old Stormont Assembly as a peacenik, known for his oratory and willingness to engage with Sinn Fein and the IRA. Without Ervine, it is said, there might never have been a Loyalist ceasefire and thus no meaningful progress towards peace in Northern Ireland. His death was mourned by political leaders as diverse as Tony Blair, John Major, Bill Clinton, Bertie Ahern and Gerry Adams.

Gerry Dawe did all the right things. He took his A-levels, studied English at the University of Ulster and ended up teaching at both Trinity and University College Galway. Along the way, which included a visiting professorship at Boston University, he became an award-winning poet and director of the Oscar Wilde Centre for Irish Writing. He died earlier this year following a lengthy illness, to be recalled by The Guardian for having pioneered the idea of a Protestant imagination in modern Ireland.

To my shame and embarrassement, I only found out about Eric Bell this week. For it turns out that after leaving Orangefield he played lead guitar in Them before heading south to Dublin where he met up with Phil Lynott to co-found the legendary Thin Lizzie. It was Bell who gave Lizzie its name, adapted from a comic-book character. In retirement, having played alongside some of the greatest stars in rock music, he set up home in West Cork.

Eric Bell strutting his stuff with Thin Lizzy

It was 44 years ago this week that Ronnie Bunting was shot dead, next to his wife, in their home in Republican West Belfast. Ronnie was an extremist in every sense. He was an old-style Trotskyite, a fervent Irish nationalist, a hard drinker and a ruthless assassin, whose leadership of the INLA in Belfast was notable for its savagery. He was also one of my two best friends at school and we remained in contact for several awkward years thereafter. Given that he was only 34 when he died, riddled with bullets, it is possible that he might eventually have gone the David Ervine route. But I doubt it.

In the class photograph at the top of this piece, taken when we were, I think, 16, Bunting – who else? – is the one giving the thumbs up to someone out of the picture. I am the demure-looking, lanky boy third from the left in the middle row. But even without the photographer’s prompt, I can still picture them all. Good lads. Born at a bad time.

But pictures can deceive. Not to bore you (overmuch), I will say only that I was expelled from Orangefield in 1967 after a “difficult” couple of years related to my perceived role as consigliere to Bunting. Subsequently, with my number still on his rolodex, I dropped out of not one, but two universities, being educated, as I like to put it, to an extent if not to a degree. Luckily for me, the Cork Examiner, as it then was, and the Irish Times were not put off by my ingénue foolishness and offered me the chance to redeem myself for which I remain grateful to this day. The result, after 50 years scribbling in Dublin, London, Brussels, Bonn, Amsterdam, Jerusalem and New York, is that I am become the man you see before you today: a colossus-emeritus of the Fourth Estate, somehow living incognito in a cottage in central Brittany.

So what is the thread running through our sadly depleted ranks? It wasn’t as if any of us went to public school or Oxbridge. Orangefield in the 1960s was where you ended up if you hadn’t made it to the local grammar school. It was supposed to churn out workers for the shipyard, the aircraft factory and Belfast City Council. It wasn’t supposed to produce writers, political activists, terrorists and top-end musicians.

The headmaster, John Malone – the one who expelled me – was a classic button-down liberal whose signature achievement was the creation of a proto-comprehensive school within an education system mired in the 1940s.

His staff included several individuals keen to prove that falling at the first hurdle did not necessarily mean the end of everything. Among them were Ronnie Horner, an impeccably dressed literary perfectionist, wildly out-of-place as an advocate of classical drama; the folk-singer David Hammond, later to be an award-winning documentary film-maker; and Sam McCready, a gifted artist and champion of Irish theatre, who served for many years as Professor of Drama at the University of Maryland. In selecting us for preferment, against the interests, you might think, of the rest of the school, they did us an enormous favour. But why us? Was it chance alone?

What is strange, indeed impossible to fathom, is the fact that no one after us made much of a name for themselves in the public arena. The bubble in which we breathed free burst no later than the summer of 1969. I hasten to add that we weren’t the only boys from those days worthy of remembrance. There were many others who worked hard and helped keep Belfast from falling apart during the long years of the Troubles. But in respect of the Seven, myself included, picked out as “notable alumni,” what was it that set us apart?

I have thought about this and identified one thing we had in common. Though Ulster Protestants to a man, raised in streets and housing estates in which Catholics were entirely absent and where the idea of a 32-county Republic would have been viewed as seditious, we each had a strong sense of being Irish.

Van Morrison shared stages with The Chieftains, with whom he recorded the album Irish Heartbeat, featuring not only the title song but soulful versions of Carrickfergus and Raglan Road. He has a house in Dalkey, not far from Bono, and played sell-out concerts this year in Dublin and Cork as well as Belfast.

Brian Keenan says he was sustained during his captivity by the presence of the legendary seventeenth-century Irish harper Turlough O'Carolan, whose blindness mirrored his own loss of sight when held hostage. He was brought back from Beirut on an aircraft provided by the Irish government and subsequently, after time spent recuperating in the Mayo countryside, made Dublin his home. His second book, published out of both love and duty, was entitled simply, Turlough.

Most of Gerry Dawe’s career was spent teaching at Irish universities. He never lost his Ulster accent and in his writings frequently explored his years spent in the city of his birth. His biggest bestseller was an extended prose-poem, In Another World: Van Morrison and Belfast. But though for the second half of of his life he worked as a fellow of Trinity College, it was said of Dawe by those who knew him best that he was most at home in Connacht. His wife was from Galway, and it was in the West that they raised their family.

As a young man, searching for cultural identity, Eric Bell left war-torn Belfast for Dublin, still very much the city of The Commitments, not yet riding the back of the Celtic Tiger. Over the years, he worked closely with Phil Lynott, notably contributing the recurring guitar riff for the number-one hit Whiskey in the Jar. In the years that followed, as a member of the Noel Redding Band, he toured the world performing songs such as An Irish Boy and Clonakilty Cowboys.

David Ervine, who became something of a celebrity south of the Border, used to say that he was Irish as much as British and that his critics needed to get used to the fact. For a time, he was something of a favourite on Irish radio and television, assuring audiences that in spite of the horrors that had dominated their screens for the previous 30 years, better times lay ahead.

Ronnie Bunting, who planned and organised the murder of Margaret Thatcher’s close friend and advisor Airey Neave in the carpark of the Palace of Westminster, was, depending on your point of view, a terrorist or a freedom fighter. Either way, after a tumultuous career in which he made enemies across the entire political spectrum, he was surely destined to die for the cause.

Which, again, leaves only me. The first prize I was given at Orangefield, at the age of 14, was A Book of Ireland, a collection of of essays and poems, edited by Frank O’Connor, that still holds a place of honour on my bookshelves. Another cherished volume from my teenage years is Brendan Behan’s Ireland, an entertaining miscellany by the author of The Quare Fellow and Borstal Boy. While never in the least anti-British – my son and grandson are English – I have written for many years on the inevitability of Irish unity and, like each of the Seven, consider it natural to travel on an Irish passport.

Waiting for the demolition squad

But Orangefield? Why Orangefield? Our school was rooted in Belfast’s loyalist heartland. It was even named after the seventeenth century Prince of Orange, who defeated the Catholic pretender, James II, at the Battle of the Boyne, giving us, in the words of the song, “our freedom, religion and laws”. A number of my contemporaries undoubtedly joined such paramilitary groups as the UDA and UVF, pledging never to forsake “the blue skies of freedom for the grey mists of an Irish Republic”. It is even likely that a couple or three of those I passed every day in the school corridors committed murder “for God and Ulster”.

In considering how we Seven turned out, it is probably worth noting that we completed our schooldays before the first, acrid whiff of the Troubles, which began in 1969. But was there something in the air, and if there was, why did it come and go within a seven-year span, never to return? I doubt I will find the answer, but it continues to intrigue me.

In 2014, Orangefield, which by then had become something of a co-educational backwater, was closed due to a fall in student numbers and an apparent failure to meet academic targets. Mr Malone would have been aghast. The buildings were later demolished, having in the meantime served as a set for the dystopian BBC police drama, The Fall. Ironically (or not), the site has recently been identified as the favoured location for a new Irish language primary school, the first of its kind in Protestant East Belfast for several centuries. As you might expect, I am delighted. I just hope that the project goes ahead. It would be a fitting epilogue for a story otherwise lost in time.

Seems to me that colossus-emeritus is a title worth having. Having failed to earn it, I think I will steal it.